In the last chapter, we evaluated the importance of business quality to Canopy’s investment approach and its association with excess returns. However, companies recognised as quality often command premium valuations. Business quality alone provides no protection against the risk of overpaying. Consequently, valuation is also of critical importance.

The relationship between prices and returns

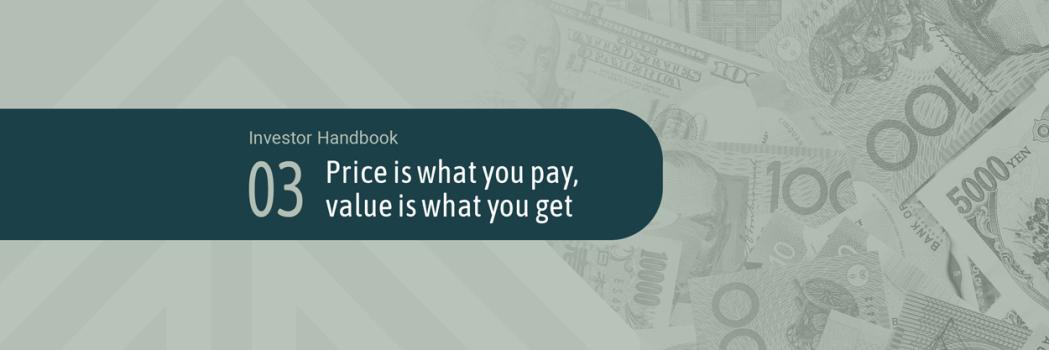

It is intuitive that higher prices correspond with lower future returns. As shown in the charts below, this has been evident for both small and large-caps in the US for at least the last 25 years.

Source: Canopy Investors, S&P, FactSet. P/E is calculated as the monthly index value divided by 12-month forward consensus earnings, beginning on 31/12/1999. Return is calculated as the forward 120 month (10 year) annualized total return.

Fama and French (1992) similarly found that value (proxied by the book-to-market ratio) is associated with excess returns, and there is a body of research suggesting the quality factor is enhanced by adding a “value tilt”.1

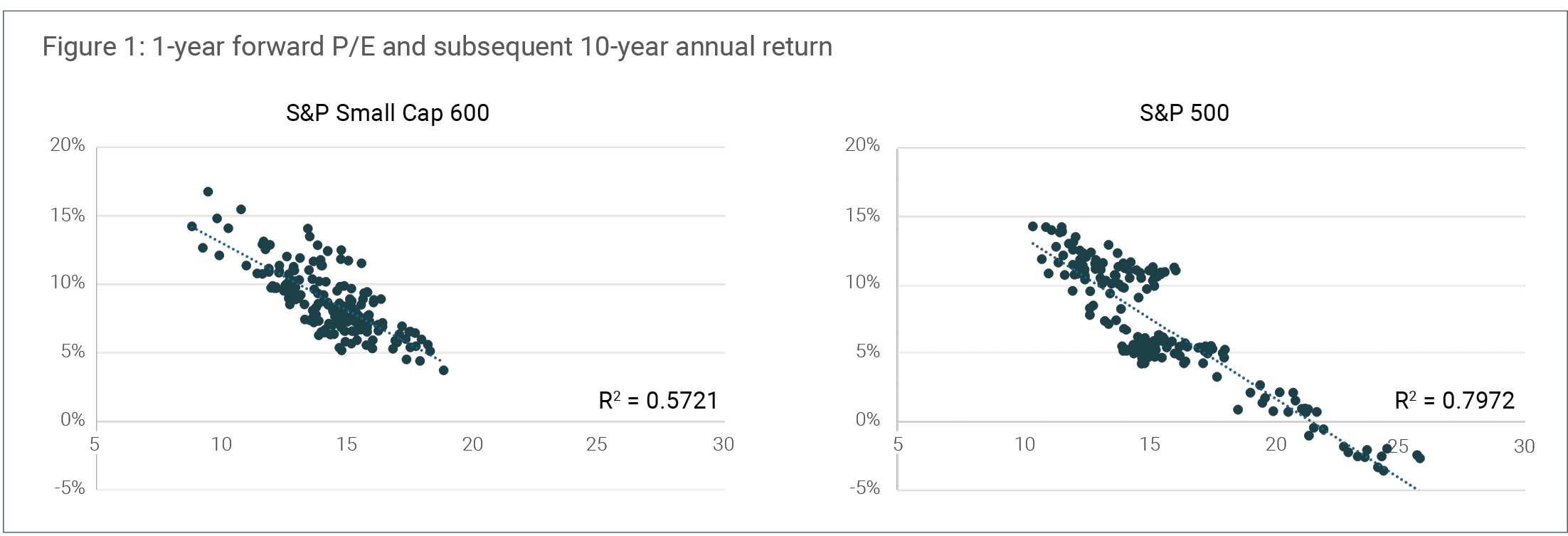

At the stock level, there are countless examples of objectively high-quality companies turning out to be poor investments - not because their business prospects weren’t excellent, but because they were overpriced to begin with. Howard Marks often points to the Nifty Fifty, which were a collection of brand-name, large-cap US stocks favoured by investors in the 1960s and early-1970s for their robust growth prospects. However, the stock prices of this cohort declined heavily during the stock market crash of 1973–1974. Coca-Cola, for instance, fell ~65% from its peak in mid-1972, and took a decade to recover to its previous high. Similarly, investor enthusiasm at the advent of the internet in the late 1990s - much of which was ultimately justified - drove Cisco's share price to a level it has not surpassed since, despite its earnings per share having increased nearly tenfold over the past 25 years.

Source: Canopy Investors, FactSet. We have adjusted Cisco’s 2018 reported EPS to exclude a charge related to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

There were similarities again in 2020 and 2021, with many companies that experienced a COVID-fuelled surge in demand, and investor enthusiasm, subsequently declining by over 90%. For example, the share price for Zoom Communications, which sells video conferencing software, fell ~85% in the two years following its peak in October 2020.

Behavioural challenges

Why do investors find it so tempting to overpay? In our view, maintaining valuation discipline is emotionally taxing in ways that few other investment principles are.

- During bull markets, pressure to abandon price discipline grows, as investors watch others profit from higher and higher prices. Social media has arguably turbo-charged this fear of missing out (‘FOMO’) by providing constant exposure to others' apparent success and creating an illusion of widespread, easy profits.

- The temptation to overpay is often compounded by the human tendency to create narratives that justify ever-higher prices. As John Templeton observed, “the four most dangerous words in investing are: ‘this time it's different.’” A good idea taken too far can form the foundation of a market bubble.

- There is often also intense institutional pressure to stay invested during rising markets. Chuck Prince, the former CEO of Citigroup, typified this pressure on the eve of the Great Financial Crisis when he said: “as long as the music is playing, you've got to get up and dance.”

Our approach

Our approach to valuation is guided by a few fundamental principles, with the goal of generating double-digit returns through an economic cycle:

- We only invest when we’ve determined there is a sufficient margin of safety. That is, when the stock is trading at a sufficient discount to our estimate of intrinsic value to protect against analytical errors and unforeseen risks.

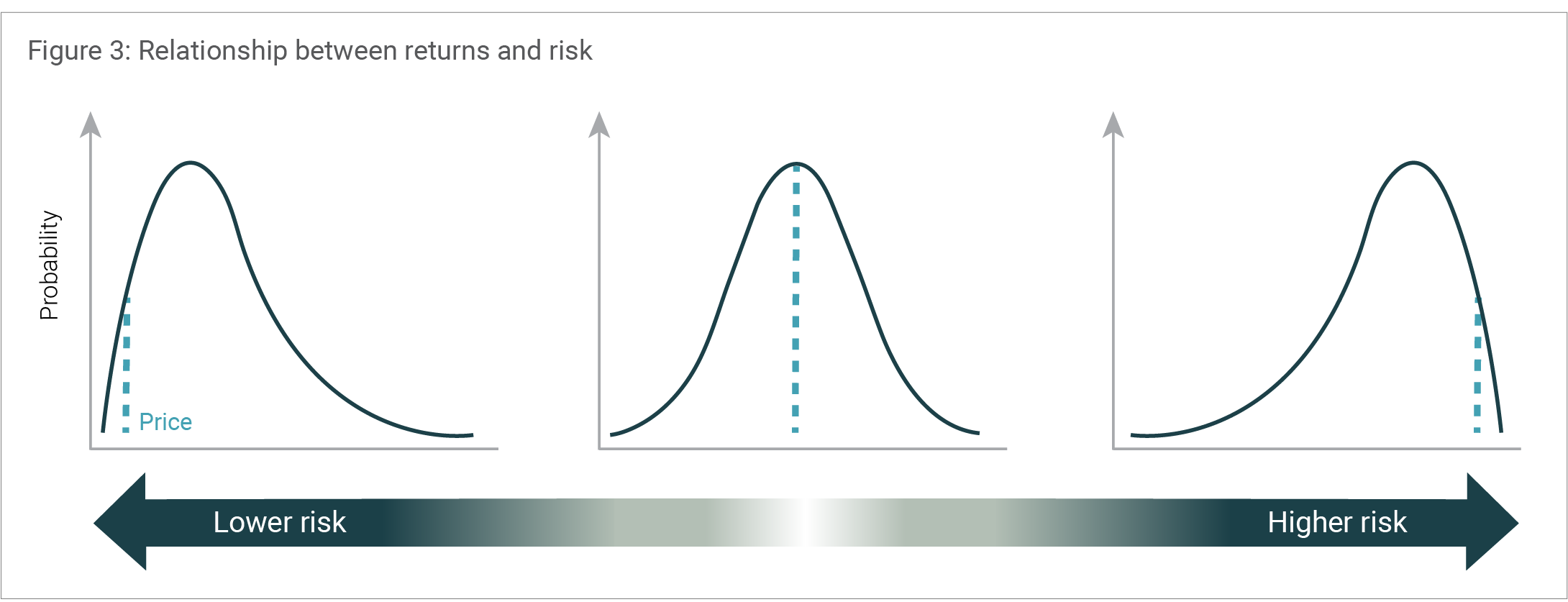

- We believe that valuation estimates are best viewed as a range of potential outcomes rather than as single point estimates. So we assess both upside and downside cases for all investments.

- We are at least as focused on the distribution of potential outcomes as on the range itself. The illustration below highlights our preference for investments with modest downside but significant upside potential (left), compared to situations with limited upside but substantial downside risks (right).

Source: Canopy Investors.

- Understanding the fundamental drivers of each company’s business model and valuation builds conviction, which is especially critical when taking a position contrary to the accepted narrative. We do this by maintaining detailed valuation estimates for companies on our watch list, using at least two different valuation approaches.

- Markets typically don’t provide free lunches, so we seek to understand the source of any undervaluation. Sometimes, the reason may be as simple as a cyclical headwind with an uncertain duration that short-term investors are unwilling to endure. Other times, investors may assume that growth will slow unreasonably quickly, or they overstate a specific risk.

While insisting on a margin of safety, we do not subscribe to the traditional notion of ’value’ investing as requiring low price-to-earnings or price-to-book ratios. Provided the above criteria are met, we are willing to invest even at optically high valuation ratios.

Investing with discipline

In sum, we believe that valuation discipline is fundamental to delivering consistent long-term investment results. We have developed a clear framework for assessing value and a team culture that encourages disciplined adherence to our valuation principles, recognising that even the best business can be a bad investment if purchased at too high a price.

Bibliography

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1992). The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns. Journal of Finance, 47(2), 427-465.

Kozlov, M., & Petajisto, A. (2018). Global Return Premiums on Earnings Quality, Value, and Size. The Journal of Portfolio Management, 44(3), 104-118.

Marks, H. (2011). The Most Important Thing: Uncommon Sense for the Thoughtful Investor. Columbia University Press. Novy-Marx, R. (2013).

The Other Side of Value: The Gross Profitability Premium. Journal of Financial Economics, 108(1), 1-28.

The content contained in this article represents the opinions of the authors. The authors may hold either long or short positions in securities of various companies discussed in the article. The commentary in this article in no way constitutes a solicitation of business or investment advice. It is intended solely as an avenue for the authors to express their personal views on investing and for the entertainment of the reader.